Documentation OACC Example

SecureTodo Example Application

This document, including the illustrations referenced within it, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

This document will illustrate how to integrate the open-source OACC security framework into a sample Java application to address several real-world authorization scenarios.

Motivation

OACC's Get Started tutorial provided the steps to install and configure OACC and showed how to define your application model, but did not go into detail on OACC's many authorization features or how to best use them to secure your application.

Using a simple example, this document will pick up where the Get Started tutorial left off and will show and explain how to integrate OACC into an application. Along the way, it will introduce several of OACC's powerful authorization features, such as permission delegation, finding resources by permission, inheritance, and post-create permissions.

The complete source code for this example application is available on GitHub under the Apache License, Version 2.0, but the most relevant sections are included and explained directly within this text. Let's get started and introduce you to this sample application.

Part I: Introducing the SecureTodo Application

To showcase OACC's authorization features and integrate them into a simple example application, a generic "Hello World" just won't cut it. Instead, the sample SecureTodo app we'll use here builds on the ideas of TodoMVC and the Todo Backend Project, which simply use a todo-list implementation as a coding example to illustrate the features of a framework.

SecureTodo is an adaptation of an example todo-list application that allows a user to create, view, edit and mark as completed a list of todo items. To live up to its name, we'll secure todo lists by adding authentication and authorization: users can sign up and create their own private todo lists. In addition, users will be able to selectively share their todo-items with other users.

SecureTodo API Features

In brief, the SecureTodo API should allow:

- user sign-up

- creation of a todo item for an authenticated user

- retrieval of a user's todo list: all todo items created by or shared with an authenticated user

- editing a todo item for an authenticated user

- marking a todo item as completed for items created by or shared with an authenticated user

- sharing an authenticated user's todo item with another user

Design Decisions

Here's a quick outline of the most important design decisions regarding our SecureTodo application, which stem from the desire to keep the example illustrative, yet easy to understand.

For simplicity's sake let's omit the capabilities of deleting todo items or changing their order. Similarly, to keep the code brief and focused on OACC integration, let's only look at a REST-ful SecureTodo API (specifically a RMM Level 2 implementation), instead of an example with a full-blown graphical interface. Let's use Dropwizard as the Java web services framework, because it is simple, self-contained and, as it claims, lets us "focus on getting things done". If you're unfamiliar with Dropwizard, feel free to reference its Getting Started guide and manual.

One of the goals of this example application was to allow you to not only follow along in the source code, but also to provide you a simple way of running the code without having to deal with database setup, configuration and other steps already covered in OACC's Get Started tutorial. Dropwizard solves this for us by letting me pre-configure in-memory database models using Liquibase migrations that will get executed during application startup.

Lastly, our SecureTodo application will only employ Basic Authentication over https. It is sufficient for our purposes of illustrating OACC integration and it is a simple enough protocol you're likely already familiar with.

Application and Security Models

Next, let's take a look at what SecureTodo's application domain and security model look like.

Application Domain

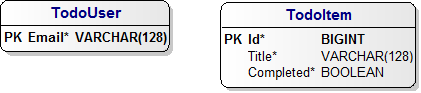

As mentioned earlier, the SecureTodo application lets users sign up and create their own private list of (shareable) todo items. We really only need two entities in our application domain to cover this requirement: TodoUser and TodoItem.

A TodoUser simply has a single email address field, which uniquely identifies each user. A TodoItem will contain a unique numerical id field, a textual title field to capture what the todo item is about, and a boolean completed flag to indicate that the todo item has already been done. The complete ER diagram for the corresponding TodoDb tables looks as follows:

Wait - how are we going to authenticate the user? Won't we need to store a password hash somewhere? And how will we associate todo items with users? Where are the relationships in this ER diagram?

Can you believe this is really all we need to model our application domain? The beauty of using OACC to manage security, is that we won't need to pollute our domain model with authentication or authorization artifacts. Let's have a look at the security model, next.

Security Model

OACC allows you to secure individual domain objects within your application. To do so, you have to define or "register" the parts of your application model you'd like to secure in OACC, as described in detail in the Get Started tutorial. The SecureTodo application model for OACC has already been pre-configured and registered within the Dropwizard migrations for our app's in-memory database.

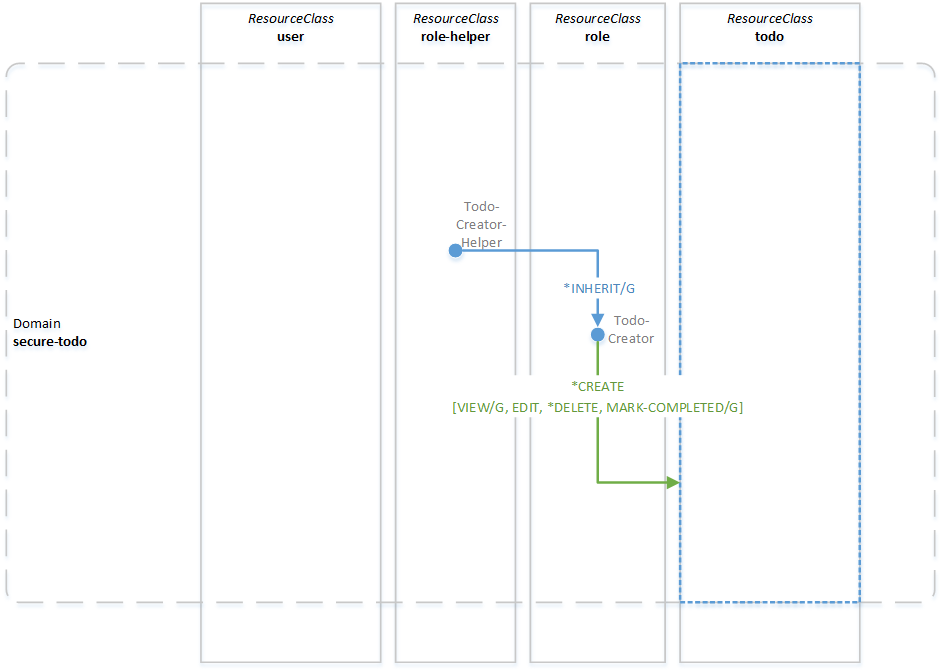

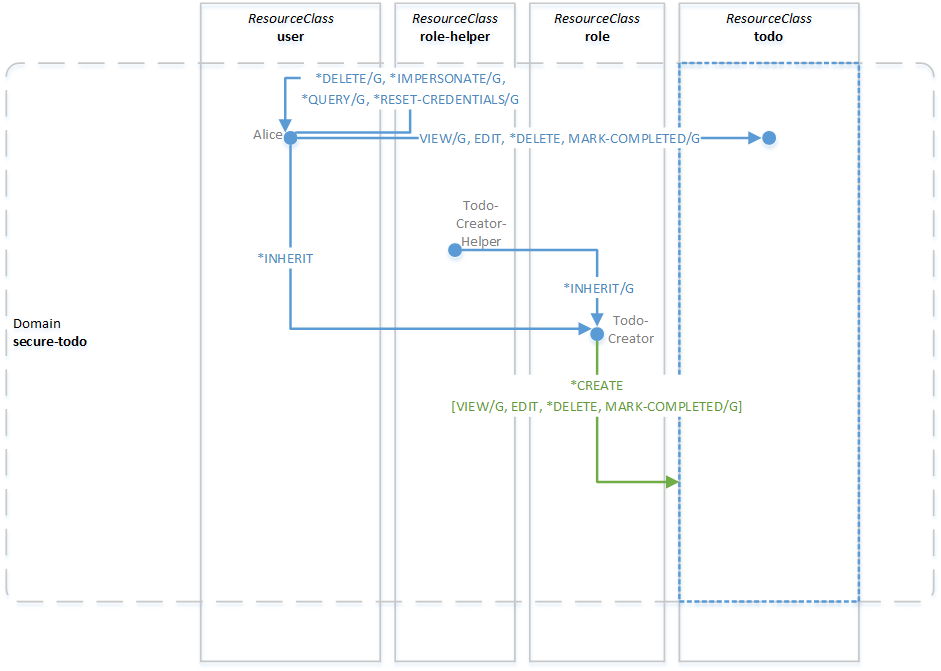

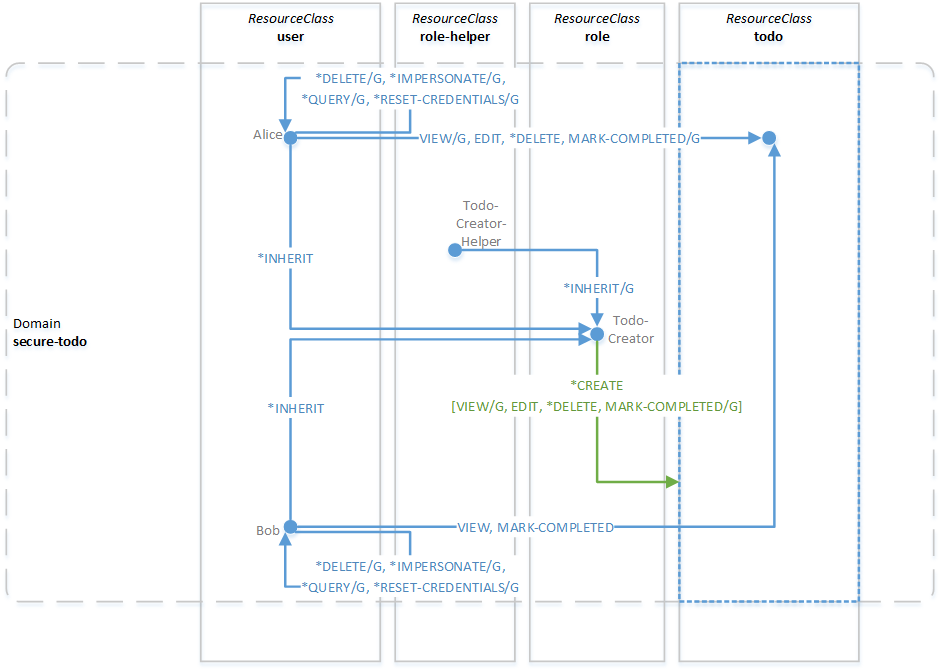

The figure below illustrates what the security model looks like right after you start up the SecureTodo Dropwizard application. Blue dots represent resources, blue arrows represent resource permissions and green arrows represent create-permissions including the specified post-create permissions. The rest of this section describes that security model, without showing the OACC calls used to initialize it.

Domains

Within OACC, every resource exists inside a domain. Domains serve to scope groups of resources, and most security operations in OACC work within the context of a specified domain.

SecureTodo has no need to scope multiple groups of resources (it's neither multi-tenant, nor does it manage hierarchies of domain objects). Thus a single domain - conveniently named secure-todo - is sufficient and will contain all the OACC resources for this application.

Resource Classes

The SecureTodo application should support user sign-up and authentication, and should secure a user's todo items. This means that we need at least two resource classes to represent both users and todo items as secured objects.

-

Resource class

user(authenticatable:true, unauthenticatedCreateAllowed:true): Resources of typeusershould be able to get created from an unauthenticated context, because users should be able to sign themselves up (as opposed to getting created by some kind of admin user). Furthermore, user resources need to be able to authenticate, e.g. to log in after having signed up. -

Resource class

todo(authenticatable:false, unauthenticatedCreateAllowed:false): Resources of typetodo, on the other hand, should not be authenticatable, nor should they be created from an unauthenticated context - it is always an authenticated user that will create a resource representing a todo item.

Role and Helper Resources

The diagram above shows two more resource classes defined for our application: role and role-helper. These exist to facilitate user permission management.

The todo-creator resource of type role models an RBAC role that has create-permission for resources of type todo in the secure-todo domain. In other words, the todo-creator role has permission to create todo items. All SecureTodo users should be "assigned" that role. In OACC you can model role assignment by having one resource "inherit" all permissions from another resource by granting it the *INHERIT permission. In our case a user would inherit from the todo-creator role. The *INHERIT permission is one of the built-in system permissions that are automatically available to all resource classes. Built-in system permissions always start with an asterisk *.

The only purpose of the todo-creator-helper resource is to grant the inherit-permission on the todo-creator role to any user resource. That's why *INHERIT is the only permission todo-creator-helper has, and why it has it with the grant option (indicated by the /G in the diagram). The grant option controls permission delegation: the ability to assign your permission to someone else. OACC is the only framework that natively supports permission delegation control at the authorization level. We'll revisit this in more detail later, when we cover user creation and sharing of todo-items.

Resource Permissions

Let's take a closer look at the user and todo resource classes representing the domain objects we want to secure. In OACC, you can define the types of permissions available for each resource class. Those permissions are String-based and can represent any operation you need to secure. Note that OACC already provides functionality to deal with the life-cycle of resources, so you typically do not have to define *CREATE or *DELETE permissions for any resource class.

We're not supporting any operations on users (aside from sign-up) right now, so we won't need any custom permissions for the user resource class.

For the todo resource class, on the other hand, the following permissions have been defined:

VIEW- to view a todo itemEDIT- to edit a todo item, including its title and completed flagMARK-COMPLETED- to set the value of a todo item's completed flag only

You might already have noticed in the figure above that the todo-creator role has all of the above permissions defined as post-create permissions to the todo resource class. This means that someone in that role will automatically get assigned those permissions to any todo resource they create. Both the VIEW and MARK-COMPLETED permissions will be assigned with the grant option, which we'll use to share todo items between users, later.

This concludes Part I, which introduced the SecureTodo example application, described its security model and touched on how to model roles in OACC. Let's move on to part II, where we'll get our hands dirty and create some users!

Part II: User Creation & Role Assignment

In part I of this document, we looked at the SecureTodo example application and reviewed its features. In this part, we'll take a close look at one of those features: user creation.

Requirements

One of the fundamental features of SecureTodo is that users should be able to sign themselves up with an email address as their unique login identifier. One possible way to model this feature is with the following RESTful operation:

POST /users

Content-Type: application/json

This operation to create a new user resource requires a message body of content type application/json with the following structure:

// TodoUser

{

"email": "email_string",

"password": "password_string"

}

The /users REST resource endpoint

Have a quick glance at TodoUserResource.java to see how to define the aforementioned operation in Dropwizard, which uses Jersey (the JAX-RS reference implementation) as the web service framework to expose RESTful APIs.

@Path("/users")

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class TodoUserResource {

private final TodoUserService todoUserService;

public TodoUserResource(TodoUserService todoUserService) {

this.todoUserService = todoUserService;

}

@POST

public TodoUser createUser(TodoUser todoUser) {

return todoUserService.createUser(todoUser);

}

}

The createUser() method of the TodoUserResource lets Dropwizard handle marshalling of the incoming JSON data from the POST request to the TodoUser parameter, and then simply delegates to the service layer, which we'll look at in more detail, next.

Service Layer

In our TodoUserService, we essentially want to add an entry into SecureTodo's TodoUser table and register a corresponding authenticatable user resource in OACC to handle our authentication and authorization needs for that user. Thus, the TodoUserService uses a data access object to interface with the application domain's database tables, as well as a factory from which to retrieve an OACC AccessControlContext, which is the main interface to OACC's API. To instantiate the OACC context, the factory simply picks up the required sqlProfile and schemaName from the oacc section of the application's Dropwizard configuration file (secure-todo.yml).

public class TodoUserService {

public static final EmailValidator EMAIL_VALIDATOR = new EmailValidator();

private final TodoUserDAO todoUserDAO;

private final AccessControlContextFactory oaccFactory;

public TodoUserService(TodoUserDAO todoUserDAO, AccessControlContextFactory accessControlContextFactory) {

this.todoUserDAO = todoUserDAO;

this.oaccFactory = accessControlContextFactory;

}

// ...

}

The createUser() service method that the TodoUserResource delegates to is shown below:

public TodoUser createUser(TodoUser todoUser) {

assertTodoUserIsValid(todoUser);

// normalize the user's email address to lowercase

final TodoUser newTodoUser = new TodoUser(todoUser.getEmail().toLowerCase(),

todoUser.getPassword());

// let's add the oacc resource first, which will implicitly check if email already exists and if password is valid

final AccessControlContext oacc = oaccFactory.build();

final Resource userResource = createUserResource(newTodoUser, oacc);

try {

// assign role(s) to new user

assignUserRoles(userResource);

// now let's add the new todoUser as an entity in the app model

todoUserDAO.insert(newTodoUser);

}

catch (Exception e) {

// something went wrong, so let's try to undo the oacc resource creation

oacc.deleteResource(userResource);

throw e;

}

return new TodoUser(newTodoUser.getEmail());

}

The createUser() service method starts by validating its input with a call to assertTodoUserIsValid(). We won't need to study the input validation method in any detail, but we'll note that all our service methods perform input validation as a first step. Now let's get to the heart of user creation.

In brief, the service method normalizes the user's email address to lowercase, so that a user's unique identifier is treated in a case insensitive manner, then creates an OACC user resource, assigns it the appropriate authorization role(s), adds a new row into the TodoUser table, and finally returns a representation of that new user.

Creating a user resource using OACC

Using OACC to create a user resource from within our service looks like this:

private static Resource createUserResource(TodoUser todoUser, AccessControlContext oacc) {

final Resource userResource;

try {

userResource = oacc.createResource(SecurityModel.RESOURCECLASS_USER,

SecurityModel.DOMAIN_SECURE_TODO,

todoUser.getEmail(),

PasswordCredentials.newInstance(todoUser.getPassword()));

}

catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

if (e.getMessage() != null && e.getMessage().contains("External id is not unique")) {

final String msg = String.format("A todo user with email %s already exists", todoUser.getEmail());

throw new IllegalArgumentException(msg);

}

else {

throw e;

}

}

return userResource;

}

Creating a user resource is essentially just a single call to OACC's createResource() method, for which we specify the resource class and domain in which our new resource should be created. For simplicity, the names of our domains and resource classes are already defined as String constants in a class called SecurityModel, to make them reusable throughout our code. In addition to domain and resource class, we provide an external identifier, namely the user's unique email address, to be able to reference that resource later on. Lastly, we provide the user's password as credentials, because resources of class user are authenticatable. OACC will handle the secure storage of password-based credentials for us with its default built-in authentication provider, using salting, binding and iterative one-way hashing with bcrypt.

The rest of the createUserResource() method shown above just translates an OACC exception message for duplicate resources into a more appropriate domain-specific message stating that a user with that email address already exists.

Assigning a "role"

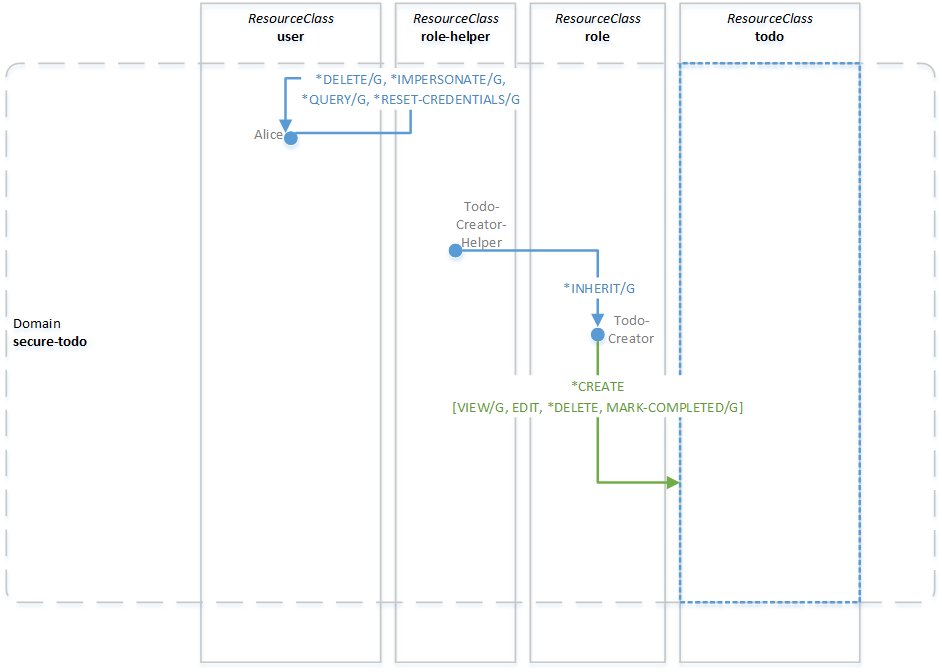

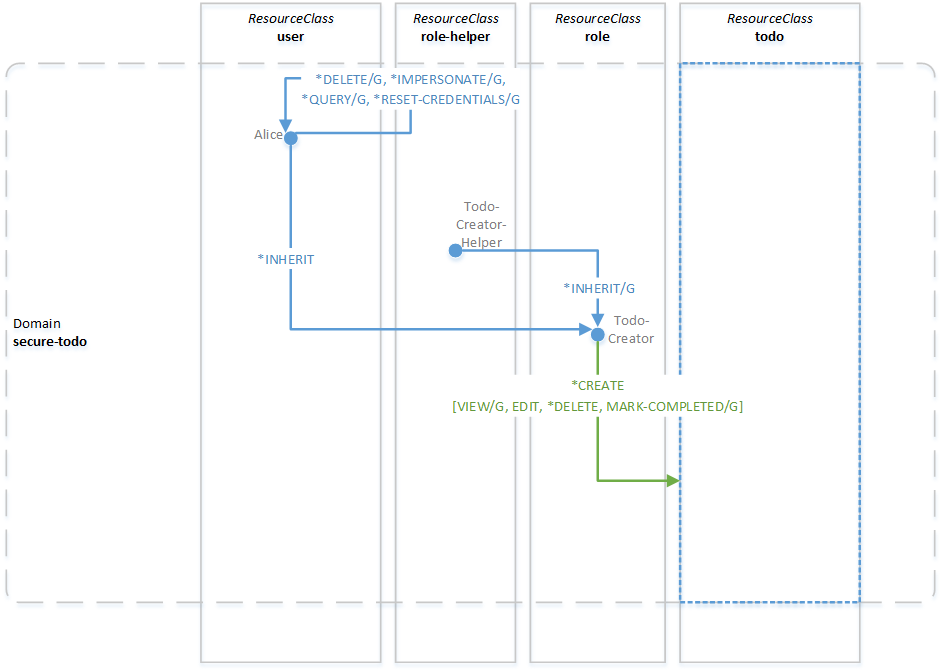

At this point, we have a resource of class user, initiated from a self-signup - in other words, created from an unauthenticated context. Resources created in such a way automatically get all the available permissions for the resource class they belong to on themselves. In our case, the only available permissions for user resources are OACC's built-in permissions, because we didn't define any custom ones. These permissions are illustrated on the user resource labeled Alice in the diagram below, which depicts the state of OACC's security graph right after Alice's self-signup. The /G after a permission denotes that she received that permissions with the grant option, meaning she is authorized to delegate it to other resources (if our application were to provide that functionality).

What we really want, though, is for our user resource to be able to create, view, edit and mark as completed her todo items. As mentioned in part I, our security model includes a resource of class role with the proper permissions for that exact purpose. Our next step thus is to "assign" that role to Alice.

At this point, we're still in an unauthenticated context from OACC's point of view, because Alice signed herself up (as opposed to an admin logging in and adding her, for example). So how do we go about assigning permissions to a resource when no one is logged in or has permissions to do so? In our case, we use the todo-creator-helper resource we briefly mentioned in part I. It is meant to be an internal helper resource with the sole purpose of assigning a specific role to a user resource. This means we need an OACC context that is authenticated as that helper resource, in order to grant the *INHERIT permission it has on the todo-creator role to Alice, our user resource, as shown below.

private void assignUserRoles(Resource userResource) {

// assign role to new user so they can create todoItems

final AccessControlContext roleHelperContext = oaccFactory.build();

roleHelperContext.authenticate(SecurityModel.RESOURCE_ROLEHELPER_TODOCREATOR,

SecurityModel.CREDENTIALS_ROLEHELPER_TODOCREATOR);

roleHelperContext.grantResourcePermissions(userResource,

SecurityModel.RESOURCE_ROLE_TODOCREATOR,

SecurityModel.PERM_INHERIT);

}

When a resource has a certain permission and assigns it to another resource so that the other resource has the same permission, we call it permission delegation, and it requires the grant option (indicated by /G in the diagrams) on that permission. Without the grant option, a resource cannot delegate their permission to another resource. Our todo-creator-helper resource has the *INHERIT /G permission (i.e. with the grant option), but only needs to delegate the core permission to Alice without the grant option, because she won't need to assign the permission to other users.

After assigning the todo-creator role to Alice, our security graph looks like this:

On a side note: If Alice hadn't signed herself up, but had been created by some sort of admin that was authorized to create user resources, that admin resource would likely also have had explicit permission to assign the

*INHERITpermission on the required role to Alice, and she would thus have had the permissions we want her to have. With self-signup users, we don't have anyone that was authenticated and authorized to grant Alice the permissions she needs, hence the need to introduce a role-helper.

Give it a try and run the example below!

Running the example

To build the Dropwizard application jar, run the maven mvn package command from the sample app directory (or use your IDE's equivalent). Then start the Dropwizard application with the following command:

java -jar target/secure-todo-1.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar server secure-todo.yml

POST a new SecureTodo user using the curl command below (or use a tool of your choice):

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X POST -d '{"email":"alice@oaccframework.org", "password":"secret"}' \

https://localhost:8443/users

And you should get a successful response that looks similar to this:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 02:58:18 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 35

{"email":"alice@oaccframework.org"}

This concludes part II, user creation; next we'll take a look at how to let OACC handle authentication for us.

Part III: Authentication and Implicit Authorization

In part II of this document, we created users in the SecureTodo example application. In this part, we'll create todo items and look at how to handle authentication in general, and also how implicit authorization comes into effect for the todo item creation.

Requirements

The most important feature of SecureTodo is of course the ability to create todo items as an authenticated user. These todo items are secured in the sense that only users who are authorized are allowed to view or change them, which is why the users need to be authenticated. One possible way to model this feature is with the following RESTful operation:

POST /todos

Content-Type: application/json

Authorization: Basic base64EncodedUsernameAndPassword=

This operation to create a new todo item resources requires a message body of content type application/json with the following structure:

// TodoItem

{

"title": "title_string",

"completed": false

}

Note that the completed property is optional and will default to false upon creation of a todo item.

As mentioned in the design decisions of part I, we'll use HTTP Basic Authentication because it is sufficient enough for our purposes of learning about OACC and because it is a simple protocol that most people are already familiar with.

Let's start from the bottom up this time and take a look at the service layer first.

Service Layer

In our TodoItemService, we essentially want to add an entry into SecureTodo's TodoItem table and register a corresponding todoItem resource in OACC because we need todo items to be secured objects in our application. Thus, the TodoItemService uses a data access object to interface with the application domain's database tables. In addition, each service method will use an already authenticated OACC AccessControlContext that's passed into the service method, as described later. This is a different approach than in the user service, where we used a factory to get an unauthenticated OACC context.

public class TodoItemService {

private final TodoItemDAO todoItemDAO;

public TodoItemService(TodoItemDAO todoItemDAO) {

this.todoItemDAO = todoItemDAO;

}

public TodoItem createItem(AccessControlContext oacc,

TodoItem newTodoItem) {

assertTodoItemIsValidForCreation(newTodoItem);

// add the new todo item to our application domain table

final long newId = todoItemDAO.insert(newTodoItem);

final TodoItem todoItem;

try {

// look up the created todo item so we can return it

todoItem = todoItemDAO.findById(newId);

// register the created todo item as a secured object in OACC

oacc.createResource(SecurityModel.RESOURCECLASS_TODO,

SecurityModel.DOMAIN_SECURE_TODO,

String.valueOf(todoItem.getId()));

}

catch (Exception e) {

// something went wrong, so let's try to undo the todoItem creation

todoItemDAO.delete(newId);

throw e;

}

return todoItem;

}

// ...

}

After validating its input, the createItem() service method above first adds the new todo item as an entity in the application domain, then uses the newly created entitiy's ID as the external identifier when creating the corresponding todo item resource in OACC. If anything goes wrong during resource creation, we attempt to roll back the creation of the todo item entity in the application domain.

Next we'll dive into the OACC resource creation in a bit more depth.

Create-permissions

The call to OACC's createResource() method implicitly checks that its authenticated resource actually is authorized with the built-in *CREATE system permission to create a new resource of the specified class in the specified domain. Recall from part II that a user resource inherits the *CREATE permission on the required resource class and domain from the todo-creator role resource during user creation. As far as authorization verification is concerned, we're set.

A novel feature of OACC is automatic permission assignment through create-permissions, which not only control what kind of resources a subject may create, but also define exactly what permissions they would get on a new resource after creating it - defined once, permissions are automatically assigned to a resource creator, without the need for explicit API calls.

As part of the create-permission, the todo-creator role also has post-create permissions of VIEW/G, EDIT, *DELETE and MARK-COMPLETED/G on the todo resource class in the secure-todo domain. A user (such as Alice), who was assigned the todo-creator role, will thus be authorized to view, edit, delete and mark as completed any new todoItem she creates, without us having to call grantResourcePermission() explicitly. The complete security graph after todo item creation is illustrated in the diagram below.

Next, let's take a look at how we get an authenticated OACC context as a parameter to the createItem() service method.

Authentication

At this point, we know that we want to call our service layer method from the REST resource endpoint handler, and that the service method expects an authenticated OACC context. We have already decided that our REST endpoint should employ the HTTP Basic Authentication protocol.

Let's make use of a Dropwizard authentication filter on our REST endpoint. The filter will provide the Basic Authentication credentials to an authenticator strategy class that we'll implement. The strategy class' only method is expected to process the credentials and return a Principal that the filter then injects into the endpoint handler.

All we need to do in the strategy class is to verify the credentials and make an authenticated OACC context available in the returned Principal, so that the endpoint handler can pass it on to the service layer. Well the first part is easy, because the authenticate() method of an OACC AccessControlContext requires credentials and verifies them. The latter part we solve by implementing a custom OaccPrincipal that simply stores the authenticated OACC context.

Here's the implementation of the authenticator strategy that we'll register with the authentication filter:

public class OaccBasicAuthenticator implements Authenticator<BasicCredentials, OaccPrincipal> {

private final AccessControlContextFactory oaccFactory;

public OaccBasicAuthenticator(AccessControlContextFactory accessControlContextFactory) {

this.oaccFactory = accessControlContextFactory;

}

@Override

public Optional<OaccPrincipal> authenticate(BasicCredentials basicCredentials) throws AuthenticationException {

OaccPrincipal oaccPrincipal = null;

if (basicCredentials != null) {

// the email from the basic auth username is the external id of the oacc user resource

final String normalizedEmail = basicCredentials.getUsername().trim().toLowerCase();

final AccessControlContext oacc = oaccFactory.build();

try {

// authenticate the oacc context and store it in a custom Principal

oacc.authenticate(Resources.getInstance(normalizedEmail),

PasswordCredentials.newInstance(basicCredentials.getPassword().toCharArray()));

oaccPrincipal = new OaccPrincipalImpl(oacc);

}

catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

// swallow exception to not divulge any information

}

catch (com.acciente.oacc.AuthenticationException e) {

// swallow Auth exception to not divulge any information

}

}

return Optional.ofNullable(oaccPrincipal);

}

}

If OACC's authentication fails, either because it couldn't find the user or the password was incorrect, we swallow the cause, return a null Principal and let Dropwizard handle responding with a 401 Unauthorized from the REST endpoint, which we'll look at next.

REST resource endpoint

Now that we have a service method and a way to create an authenticated OACC context using HTTP Basic Authentication, we're ready to implement the /todos resource endpoint for creating todo items. Have a look at TodoItemResource.java below.

@Path("/todos")

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class TodoItemResource {

private final TodoItemService todoItemService;

public TodoItemResource(TodoItemService todoItemService) {

this.todoItemService = todoItemService;

}

@POST

public TodoItem createItem(@Auth OaccPrincipal oaccPrincipal,

TodoItem newTodoItem) {

return todoItemService.createItem(oaccPrincipal.getAccessControlContext(), newTodoItem);

}

}

The @Auth annotation on the first parameter of the createItem() method triggers the Basic Authentication filter that injects the principal containing the authenticated OACC context, as described in the previous section. The method also uses Dropwizard to marshall the submitted JSON data from the POST request to the newTodoItem parameter, and then simply delegates to the service layer we introduced earlier.

Running the example

Try creating a new todo item to "call mom" using the curl command (or equivalent) below:

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-u alice@oaccframework.org:secret \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X POST -d '{"title":"call mom"}' \

https://localhost:8443/todos

And you should see a successful response similar to the following, that includes the full representation of the todo item, including its generated identifier (and URI path):

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 02:58:45 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 62

{"id":1,"title":"call mom","completed":false,"url":"/todos/1"}

That's it for part III, in which we covered user authentication, todo item creation with implicit authorization checks and automatic permission assignment. In the next part, we'll delve into more OACC features such as query methods and detailed (explicit) authorization verification.

Part IV: Query Methods and Explicit Authorization - Getting a User's TodoItems, Sharing and Editing a TodoItem

In part III of this document, we authenticated and created todo items as secured objects in our SecureTodo example application. In this part, we'll take a more detailed look at OACC's authorization features and learn how to look up resources by permission, as well as verify authorization and grant permissions explicitly.

Getting a list of todo items for a user

The next feature of SecureTodo we'll tackle is the ability to retrieve all todo items created by or shared with an authenticated user.

Requirements

Getting a user's todo items could be modeled with the following RESTful operation:

GET /todos

Authorization: Basic base64EncodedUsernameAndPassword=

We would expect such an operation to produce a response of content type application/json that is an array of todo items, with the following structure:

[

{

"id": 1,

"title": "title_string",

"completed": false

}

]

REST resource endpoint

The corresponding /todos REST resource endpoint (in TodoItemResource.java) to retrieve todo items for an authenticated user looks as follows.

@Path("/todos")

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class TodoItemResource {

// ...

@GET

public List<TodoItem> findByAuthenticatedUser(@Auth OaccPrincipal oaccPrincipal) {

return todoItemService.findByAuthenticatedUser(oaccPrincipal.getAccessControlContext());

}

// ...

}

We'll employ the same kind of authentication as discussed in part III, using the @Auth annotation, and then simply delegate to the service method to get and return the list of todo items, which Dropwizard will translate into the appropriate JSON array form, based on the @Produces class annotation.

Service Layer

The service method in TodoItemService.java that retrieves the todo items the authenticated user has access to, is shown below.

public List<TodoItem> findByAuthenticatedUser(AccessControlContext oacc) {

// find all todoItem resources which the authenticated user is authorized to view

final Set<Resource> todoItemResources

= oacc.getResourcesByResourcePermissions(oacc.getSessionResource(),

SecurityModel.RESOURCECLASS_TODO,

SecurityModel.PERM_VIEW);

// return the corresponding list of todoItems

if (todoItemResources.isEmpty()) {

return Collections.emptyList();

}

else {

// convert list of oacc resources to list of IDs from the application domain

final List<Long> todoItemIds = todoItemResources.stream()

.map(todoItemResource -> Long.valueOf(todoItemResource.getExternalId()))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// look up the todo items in the application domain table and return them

return todoItemDAO.findByIds(todoItemIds);

}

}

The first thing we do is call getResourcesByResourcePermission() on the authenticated OACC context. This is one of OACC's query methods, which returns a set of resources (of the specified resource class) on which the specified accessor resource has the specified permissions, regardless of domain. You'll often see us refer to the family of symmetric query methods, because OACC offers a similar method that operates in the reverse direction and returns a set of resources that have the specified permission(s) to the specified accessed resource. These methods are very efficient because OACC performs a targeted query into the security graph and only returns the applicable resources, without loading all resources first and subsequently filtering out the unauthorized ones.

In our case above, we're interested in finding all resources of class todo to which the current user has VIEW permission. We specify the current user as the accessor by calling getSessionResource(), which returns the context's authenticated resource (unless another resource is being impersonated). If we get a non-empty list of todo item resources, the only other thing to do is to look up the corresponding entities in the application domain by using the todo items' id values that we stored as the external id in the OACC resources.

It is worth noting that we didn't need to keep track of which todo items a user is authorized to view in our application domain tables, for example by using an "owner" field or a many-to-many association table between users and todo items. Neither did we have to check each and every todo item to determine on which ones our current user has the desired authorization, like you would within a traditional access control list implementation. The security model OACC manages for you behind the scenes was designed to provide highly efficient, fine-grained authorization functionality. This lets you focus on implementing your core business rules, and without having to pollute your application's data model with security-related information.

Running the example

Try retrieving all todo items for our user:

curl -i -k -w "\n" \

-u alice@oaccframework.org:secret \

https://localhost:8443/todos

This should produce a successful response similar to the one below:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 02:58:59 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Content-Length: 64

[{"id":1,"title":"call mom","completed":false,"url":"/todos/1"}]

Sharing a todo item

Another useful feature of our sample SecureTodo application is the ability to selectively share an authenticated user's todo item with another user. Selectively here means on a per-todo-item basis, and not that a user's entire todo list of items will automatically be shared with another user through this feature. Let's see how to utilize OACC to implement this.

Requirements

One possible way to model sharing a todo item with another user in a RESTful way would be to "associate" the other user's email address with the todo item using the idempotent PUT method on a URI that identifies the todo item and includes the email address in a query parameter, as shown below.

PUT /todos/{id}/?share_with={target-user-email}

Authorization: Basic base64EncodedUsernameAndPassword=

REST resource endpoint

The parameterized /todos/{id} RESTful resource endpoint (in TodoItemResource.java) to share a todo item with another user, is shown below; the target user is identified by an email string within an additional query parameter.

@Path("/todos")

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class TodoItemResource {

// ...

@Path("/{id}/")

@PUT

public void shareItem(@Auth OaccPrincipal oaccPrincipal,

@PathParam("id") LongParam todoItemId,

@QueryParam("share_with") String email) {

todoItemService.shareItem(oaccPrincipal.getAccessControlContext(), todoItemId.get(), email);

}

// ...

}

The @Path("/{id}/") annotation on the method, which supplements the parent path annotation on the class itself, binds the {id} part of the path to the method's todoItemId parameter annotated with @PathParam("id"). The target user's email address specified in the query parameter gets bound to the email parameter of the method with a straightforward @QueryParam annotation. For authentication, we'll continue using the @Auth parameter introduced in part III, and then we again simply delegate to the service method described next.

Service layer

The service method responsible for handling the sharing of a todo item with another user is explained below:

public void shareItem(AccessControlContext oacc,

long todoItemId,

String email) {

assertEmailIsValid(email);

// "share" todoItem with other user

oacc.grantResourcePermissions(Resources.getInstance(email.toLowerCase()),

Resources.getInstance(String.valueOf(todoItemId)),

SecurityModel.PERM_VIEW, SecurityModel.PERM_MARK_COMPLETED);

}

What does it actually mean to "share" a todo item? At the very least, the target user with whom a todo item is shared should be able to retrieve that item as part of the GET operation discussed in the previous section. Thus we know that the target user needs the VIEW permission on the todo item resource. After a target user performs a shared task, it also makes a lot of sense to let them use our application to indicate they have completed it, which is an operation controlled by the MARK-COMPLETED permission (as we'll describe in the next section).

Hence, the shareItem() service method mainly has to ask OACC to grant the target user VIEW and MARK-COMPLETED permissions on the resource representing the todo item. OACC's grantResourcePermission() method takes an accessor resource as the first parameter and an accessed resource as the second, for which we provide the target user and todo item resources, respectively. Keep in mind that there's an authenticated user resource implied in the authenticated OACC context, on behalf of which this operation is performed. You guessed it: this is just another example of permission delegation.

The OACC context passed to this method will automatically check if its authenticated user has both the VIEW and MARK-COMPLETED permission with the grant option. If so, then it will grant the target user resource the permissions to the todo item resource. A succesful execution of this feature is illustrated in the diagram below.

After Alice shares her single todo item with target user Bob, he will have both the VIEW and MARK-COMPLETED permissions directly on that same todo item resource. If either Alice or Bob mark the item as completed, both will be able to see the updated value of "completed": true for that todo item. Note that Bob does not have any permissions with the grant option on that todo item, thus he won't be able to share Alice's todo item with any other users. This was a design decision to re-illustrate permission delegation and how to control it with the grant option.

Running the example

First, create a second user, "Bob":

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X POST -d '{"email":"bob@oaccframework.org", "password":"bob123"}' \

https://localhost:8443/users

See what Bob's todo list looks like at this point, by performing a GET on /todos with Bob's credentials:

curl -i -k -w "\n" -u bob@oaccframework.org:bob123 https://localhost:8443/todos

As expected, Bob doesn't have any todo items, yet:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 02:59:37 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Content-Length: 2

[]

Now let Alice share her todo item with Bob, using the PUT operation we just defined:

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-u alice@oaccframework.org:secret \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X PUT https://localhost:8443/todos/1/?share_with=bob@oaccframework.org

If you then get Bob's todo list again with:

curl -i -k -w "\n" -u bob@oaccframework.org:bob123 https://localhost:8443/todos

You'll get:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 03:00:09 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Content-Length: 64

[{"id":1,"title":"call mom","completed":false,"url":"/todos/1"}]

Bob now has something to do!

Editing a todo item

The final feature we'll implement in SecureTodo allows an authenticated user to edit a todo item. This includes marking a todo item as completed, changing its title, or both.

Requirements

A typical way to RESTfully model editing of a todo item would be with an idempotent PATCH operation on a URI that identifies the resource, as shown below.

PATCH /todos/{id}

Content-Type: application/json

Authorization: Basic base64EncodedUsernameAndPassword=

Such an operation to edit a todo item requires a message body of content type application/json (while we patiently wait for application/merge-patch+json to become a standard) with the following structure, where at least one of the properties has to be set:

// TodoItem

{

"title": "title_string",

"completed": false

}

When only marking a todo item as completed, we expect the following message body, i.e. without title, applied using the same RESTful operation:

// TodoItem

{

"completed": true

}

REST resource endpoint

Similar to the previous section, we'll use a parameterized /todos/{id} RESTful resource endpoint (in TodoItemResource.java) to edit a todo item, as shown below; the message body containing the properties to be updated is injected as the endpoint's third parameter, patchItem.

@Path("/todos")

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class TodoItemResource {

// ...

@Path("/{id}")

@PATCH

public TodoItem updateItem(@Auth OaccPrincipal oaccPrincipal,

@PathParam("id") LongParam todoItemId,

TodoItem patchItem) {

return todoItemService.updateItem(oaccPrincipal.getAccessControlContext(), todoItemId.get(), patchItem);

}

// ...

}

Authentication with the @Auth annotation and binding the resource id to the todoItemId parameter using the @Path("/{id}/") method annotation are handled the same as in the previous sections. The updateItem() resource endpoint automatically marshalls the submitted JSON data from the patch request to the pathItem parameter, and then simply delegates to the service layer.

Service layer

The service method that handles updating a todo item's title and/or completed properties is explained below:

public TodoItem updateItem(AccessControlContext oacc,

long todoItemId,

TodoItem patchItem) {

assertTodoItemIsValidForUpdate(patchItem);

// check permission

oacc.assertResourcePermissions(oacc.getSessionResource(),

Resources.getInstance(String.valueOf(todoItemId)),

SecurityModel.PERM_VIEW,

patchItem.getTitle() != null

? SecurityModel.PERM_EDIT

: SecurityModel.PERM_MARK_COMPLETED);

// load existing todoItem

final TodoItem currentTodoItem = todoItemDAO.findById(todoItemId);

// get updated value object with new data

final TodoItem todoItem = currentTodoItem.getPatchedInstance(patchItem);

// update database

todoItemDAO.update(todoItem);

return todoItem;

}

One of the first things we require from our service method is to verify that the user authenticated in the OACC context is actually authorized to perform the requested operation. To verify if a resource has authorization to do something, OACC provides two types of methods that take a permission: has-permission-methods and assert-methods. If the resource isn't authorized, i.e. the resource does not have the specified permission, a has-permission method returns false, whereas an assert-method fails and throws a NotAuthorizedException. Either of these methods accept one or more permission arguments (as the last vararg parameter, like in our case above), and verify that the resource has authorization for all the specified permissions.

Before changing the properties of a todo item, the updateItem() service method will call OACC's assertResourcePermissions() to see if the context's session resource, i.e. the authenticated user, has authorization on the resource representing the todo item to be updated. The actual permissions that we'll verify on that item are the VIEW and either the EDIT or MARK-COMPLETED permissions, depending on wether the title or only the completed properties are to be updated. Note that this particular design implies a user with MARK-COMPLETED permission on a shared todo item can't submit the item's title as part of the operation to mark that item as completed.

After verifying authorization, we use the todo item DAO to load the actual entity, apply the "patch", and then persist the updated todo item with the DAO again, before finally returning the updated item as the response.

Running the example

First, let's have Alice update the title of her todo item:

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-u alice@oaccframework.org:secret \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X PATCH -d '{"title":"call mom on her anniversary"}' \

https://localhost:8443/todos/1

Then, let's see what happens if Bob's attempts to change the title of that same todo item that Alice shared with him:

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-u bob@oaccframework.org:bob123 \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X PATCH -d '{"title":"call mom and ask for money"}' \

https://localhost:8443/todos/1

This is what Bob gets:

HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 03:00:45 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 12

{"code":403}

As expected, Bob doesn't have authorization to change the title, and simply receives a status code of 403 - Forbidden. This is an instance of mapping an OACC exception (NotAuthorizedException) to a custom response status code using an exception mapper (AuthorizationExceptionMapper.java).

If Bob, on the other hand, just wants to mark the task as done, after completing it, he should have no problem, because he's authorized with the MARK-COMPLETED permission on that todo item:

curl -i -k --silent -w "\n" \

-u bob@oaccframework.org:bob123 \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X PATCH -d '{"completed":"true"}' \

https://localhost:8443/todos/1

If Alice then gets her todo list again with:

curl -i -k -w "\n" -u alice@oaccframework.org:secret https://localhost:8443/todos

Alice should see the updated status:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 25 Apr 2017 03:01:38 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Content-Length: 82

[{"id":1,"title":"call mom on her anniversary","completed":true,"url":"/todos/1"}]

Voilà! Thanks to Bob's help, Alice now has nothing left to do and can finally sit back, relax, and reflect on what she learned about OACC from our SecureTodo example.

Summary

Congratulations, you made it to the end of this writeup! The goal was to show and explain how to use the OACC framework to tackle real-world authorization scenarios. To achieve that, we covered a lot with our little SecureTodo sample application:

- We introduced OACC's core concepts of Resources, Domains and Permissions and illustrated how to apply them to your application domain.

- We encountered the special case of users that sign themselves up and explored how to assign permissions to them.

- We touched on how and when to model role-based access control within OACC's single access-control paradigm, while still supporting fine-grained permissions to objects on a per-user basis.

- We learned about several novel features in OACC's rich API, that are designed to help you focus on your application's business logic, instead of on manually managing authorization to your secured objects. Those features include the grant option to control permission delegation, query methods to look up resources by permissions, and automatic permission assignment with create-permissions.

Hopefully, you'll now have a better idea if and how you could use OACC in your project. For further background, a comprehensive overview of all of OACC's features is available here. If you'd like to know more about OACC's complete API, please refer to the API Overview, or to the Javadocs for even more detail.